As I prepared my keynote, “Contextualising AI in Education”, for the Council of Europe conference this week, I found myself drawn to the concept of paradoxes. Paradoxes have always fascinated me; they force us to reflect on seemingly contradictory realities and provoke thoughtful action. When it comes to AI in education, there are several paradoxes worth considering. Each of these contradictions presents both a challenge and an opportunity as we work to integrate AI into our classrooms while navigating the complexities of pedagogy, ethics and society.

Here are some of the paradoxes I have reflected on in the context of the Luxembourg education system, but which resonate far beyond our borders.

1. The paradox of innovation and tradition

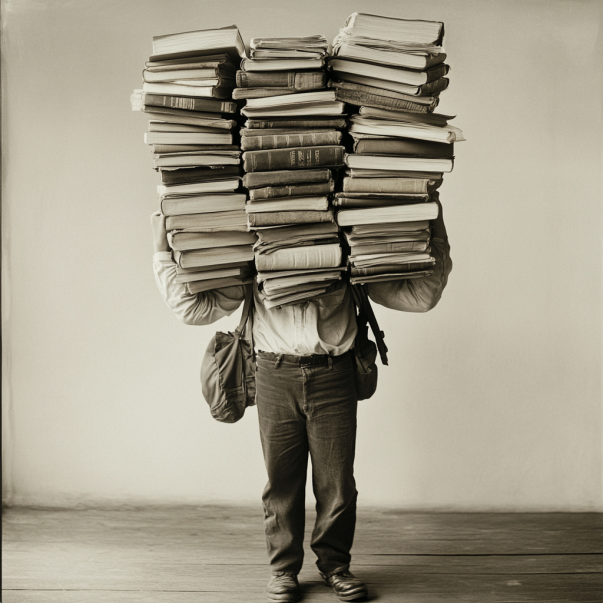

AI represents the cutting edge of innovation, advancing rapidly with each iteration. Schools, on the other hand, are traditionally slow-moving institutions, often rooted in practices honed over decades, if not centuries. The challenge is how to balance these two forces. We are told to embrace AI now – immediately – to remain relevant in an AI-driven world. But the rush to integrate this technology often leaves too little time to reflect on its long-term ethical, educational and societal implications.

In Luxembourg, where cultural and linguistic diversity is a cornerstone of our education system, the question is: How do we innovate responsibly while preserving the human-centred, multicultural teaching practices that make our system unique?

I suspect that many educators, not only in Luxembourg but around the world, feel this tension deeply. Innovation in education is not a race. It requires patience, thoughtfulness and the time to ask difficult questions about the role of technology in shaping young minds. And yet, with AI advancing so rapidly, the luxury of time is precisely what we lack.

2. The paradox of personalisation and standardisation

AI excels at personalising the learning experience – adapting to the pace, style and interests of each student. Yet most education systems, including Luxembourg’s, operate on the basis of standardised curricula and assessments. This creates a fundamental tension. Personalisation promises a world where every student can thrive according to their individual strengths, but we also need fairness and consistency in how we educate and assess students in different classrooms.

What happens when AI-powered personalised learning collides with the need for equity? Could AI exacerbate inequality by creating an education system where some students benefit more from tailored approaches, while others are held back by the rigidity of standardised expectations? These are pressing questions that need to be answered before we rush into the arms of personalised AI learning.

3. The paradox of access and exclusion

One of the great promises of AI is that it can democratise access to education. With the right tools, any student, anywhere, could theoretically learn anything. But the reality is more complex. Access to AI-driven education depends on digital literacy, devices and reliable internet access – all of which are not evenly distributed. In Luxembourg as well as in other countries, socio-economic and linguistic differences exacerbate this digital divide.

Students from more affluent backgrounds, or those who are more comfortable with technology, will naturally benefit more from AI-assisted learning. But what about those left behind? How do we ensure that AI tools empower all students equally, rather than exacerbating existing inequalities? It’s a paradox that forces us to rethink what we mean by accessibility in the digital age.

4. The paradox of multilingualism and the language bias of AI

Luxembourg’s education system is proudly multilingual, but AI often isn’t. Most AI tools, developed in predominantly English-speaking contexts, are designed to handle the world’s major languages. But what about Luxembourgish, or even French and German, which form the linguistic backbone of our schools? If AI learning platforms are dominated by English, there is a risk that national languages – considered to be low-resource languages – will be sidelined, leaving students who are not proficient in English at a disadvantage.

There is also a deeper concern here. Language is not just a means of communication; it is a way of thinking, a cultural identity. If AI erodes linguistic diversity, we risk losing the very things that make education a deeply human experience – our connection to culture, history and local context.

5. The paradox of human autonomy and AI assistance

AI can reduce the burden on teachers by automating administrative tasks, some aspects of lesson planning and even grading. But there is a risk that over-reliance on AI could undermine human autonomy. Teachers may find themselves ceding control over key pedagogical decisions to algorithms that have not been designed with local cultural and pedagogical nuances in mind.

In Luxembourg, as in other countries with its diverse student populations, it is vital that teachers retain the authority to adapt their teaching to the needs of their specific classrooms. AI should support, not dictate. The paradox is that while AI promises efficiency and support, it must never come at the expense of a teacher’s professional judgement or ability to respond to the unique dynamics of their students.

6. The paradox of creativity and dependency

AI has the potential to unleash creativity in students, giving them the tools to explore new ideas, solve complex problems and create original content. But there is a risk that students will become too dependent on AI, using it as a crutch rather than a tool. The challenge for educators is to encourage independent thinking while harnessing the strengths of AI.

How can we ensure that students in Luxembourg – and elsewhere – learn to use AI to enhance their creativity rather than replace it? It’s not just about teaching students how to use AI tools; it’s about instilling a mindset that values creativity as something that can be enhanced, but never completely outsourced, to machines.

7. The paradox of efficiency and effort

One of the key promises of AI in education is that it will make things more efficient. But, as many educators and policymakers can attest, the reality is that implementing AI in schools requires significant upfront effort. Teachers need to be trained, infrastructure needs to be upgraded, and curricula need to be aligned with AI-powered tools. In Luxembourg’s multilingual and multicultural system, these efforts are even more complex.

This is the paradox: AI is supposed to save time and effort in the long run, but the initial investment is high. And we have to ask ourselves: are we ready to make that investment? Do we have the resources, the expertise and, crucially, the time to implement AI in a way that will really benefit our students?

8. The paradox of skill acquisition and control

AI offers powerful shortcuts that streamline learning – students can quickly find answers, generate content, or automate tasks that once took time and effort. But this convenience comes at a cost: it risks undermining the development of essential skills, such as literacy and critical thinking, that underpin human control over AI systems.

The paradox is clear: AI, designed to enhance learning, can weaken the very skills needed to use it responsibly. Over-reliance on AI-generated content may prevent students from developing the cognitive skills needed to critically evaluate AI output or solve problems independently.

At the same time, mastery of both basic and advanced skills is critical to maintaining effective human oversight of AI. As AI becomes more integrated into decision-making, it’s vital that students learn to think critically, analyse information and question AI results. Without these skills, they may struggle to identify when AI is wrong, biased or ‘hallucinating’.

This paradox highlights a pressing challenge: while AI brings efficiency, it must not stifle deeper learning. AI should be a tool that enhances human capabilities and encourages students to engage more deeply with their subjects. Ensuring that AI supports, rather than undermines, essential skills requires thoughtful teaching strategies and a commitment to nurturing human intelligence alongside AI.

Conclusion

These paradoxes offer no easy solutions, but they serve as an important reminder of the complexities we face in integrating AI into education. As we look forward to a future where AI is increasingly embedded in our classrooms, it’s important to reflect on these contradictions and work towards thoughtful, balanced solutions. AI holds enormous potential for education, but only if we approach it with care, responsibility and a clear-eyed understanding of the paradoxes it presents.

AI may be the future of education, but it will only be successful if we, as educators and humans, remain in control of that future.

I’ve created a podcast based on this article using NotebookLM – it’s not perfect, but still quite impressive how it can turn an article into a conversation:

https://notebooklm.google.com/notebook/0eddee02-a3d1-43d5-818e-7135d31ddf5b/audio